PA W3 - C Programming Language Practice

If someone is reading this blog, please be aware that the writer did not consider the experience of the other readers.

After all, the most important part is about writing things down for better memorization.

Readability

Take a look at this function declaration:

1

void (*signal (int sig, void (*func)(int)))(int);

What is this? It looks like a piece of concentrated

shit. Well, if you dig deep into it, you will find that it is:- a function called

signal - the parameters of

signalare:- an

intvariable calledsig - a function pointer called

funcwhich points to a function which takes in anintvariable and returns void

- an

- the return value of

signalis another function pointer which points to another function which takes in anintvariable and returns void

- a function called

|

Very creepy code style isn’t it? How about changing it to a more readable form:

1

2typedef void (*sighandler_t)(int);

sighandler_t signal(int, sighandler_t);Now we can clearly see the meaning of this declaration.

From the example above, we can draw two conclusions:

- The readability of the code does not depend on the length of it. Short code can also have bad readability.

- Code with bad readability is difficult to understand, thus difficult to maintain and expand, not to mention debugging.

Therefore, it is important to write code with good readability.

State Machine

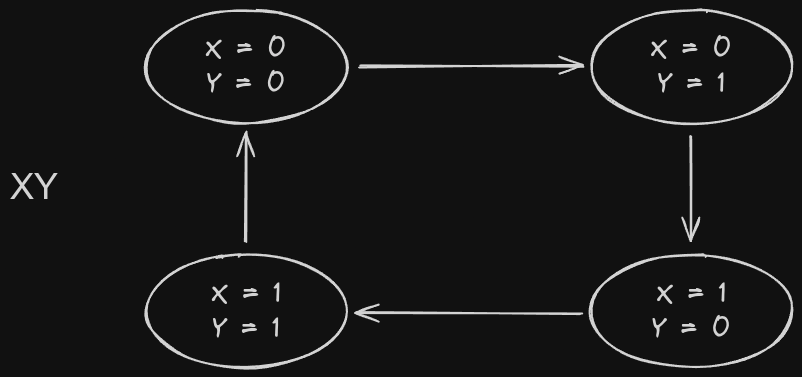

Take a look at this picture below:

The basic logic of the changes happen to

XandYcan be illustrated as follow:1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9int X = 0, Y = 0;

int X1 = 0, Y1 = 0;

while (1) {

X1 = (!X && Y) || (X && !Y);

Y1 = !Y;

X = X1; Y = Y1;

}What if we want to add another digit

Z?1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10int X = 0, Y = 0, Z = 0; // updated

int X1 = 0, Y1 = 0, Z1 = 0; // updated

while (1) {

X1 = (!X && Y) || (X && !Y);

Y1 = !Y;

Z1 = ...; // updated

X = X1; Y = Y1; Z = Z1; // updated

}We can see that there are multiple places needs to be modified, which would be a pretty nasty situation.

Consider improving the initial code to this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

FORALL_REGS(DEFINE);

while (1) {

FORALL_REGS(PRINT);

putchar('\n');

sleep(1);

LOGIC;

FORALL_REGS(UPDATE);

}

return 0;

}Now, if we want to add another digit

Z, and would like these three digits perform a loop from000to111by adding up itself by 1, we can modify the code to this:1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

FORALL_REGS(DEFINE);

while (1) {

FORALL_REGS(PRINT);

putchar('\n');

sleep(1);

LOGIC;

FORALL_REGS(UPDATE);

}

return 0;

}Noted that only macro

FORALL_REGSandLOGICare changed, the actual code remains the same. Don’t tell me that you think the update of logic is too complicated, it would be the same complicated if you stick to the original code, plus other changes around the source code.

Simulating an Operating System(OS)

Remember that, all computer system is a kind of state machine. So base on this simple 3-digit state machine shown above, we can expand it even to a real operating system(theoratically lol).

The whole thing about the ‘big loop’ which the cpu is processing can be simplified to three steps:

- fetch: read instruction from

M[R[PC]] - decode: parse the instruction according to the instruction set

- execute: execute the instruction, and the write the result to register/memory

- fetch: read instruction from

These three steps are being gone through all the time when the OS is running.

Simulating Storage

Suppose we have a computer which contains 4 registers and 16 bytes of memory. We can simulate them as the following code present:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

typedef uint8_t u8;

u8 pc = 0;

u8 R[NREG]; // register

u8 M[NMEM] = {...}; // memoryIs there a better way to simulate this scenario? Like adding names for each register?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9enum { RA, R1, ..., PC };

u8 R[] = {

[RA] = 0,

[R1] = 0,

...

[PC] = init_pc,

}This time it looks great, but if the size of the register changes, we would still have to change the

typedefforu8.Here’s serveral ways to improve this issue:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12// breaks when adding a register

// breaks when changing register size

// never breaks, but needs the definition of `r`

// even better

// does not need anything, even the calculation

enum { ra, ..., pc, nreg }

Simulating Instruction

Consider the following register and memory:

- register: PC, R0(RA), R1, R2, R3 (8-bit)

- memory: 16 bytes

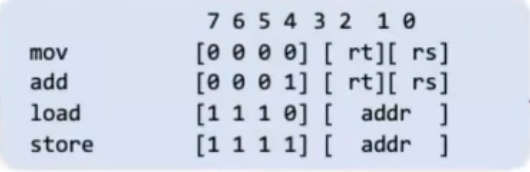

And this simple table as an instruction list.

For example, instruction

0000 1100meansmov r3 r0, which means move the value stored in theR3register toR0register.How can we perfrom this translation from the instruction to action in an actual C program? How to solve the idex issue? Well, please refer to the code below:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25void idex() {

if ((M[pc] >> 4) == 0) {

// mov instruction, mov rt rs

R[(M[pc] >> 2) & 3] = R[M[pc] & 3];

pc++;

} else if ((M[pc] >> 4) == 1) {

// add instruction, add rt rs

R[(M[pc] >> 2) & 3] += R[M[pc] & 3];

pc++;

} else if ((M[pc] >> 4) == 14) {

// load instruction, put value in specified memory address(addr) to r0

R[0] = M[M[pc] & 0xf];

pc++;

} else if ((M[pc] >> 4) == 15) {

// store instruction, put r0 to specified memory address(addr)

M[M[pc] & 0xf] = R[0];

pc++;

}

}

int main() {

while (!is_halt(M[pc])) {

idex();

}

}This code is a little hard to understand when reading, cuz it uses a lot of decimal numers.

- For example,

(M[pc] >> 4) == 14. This14at the right of the equal sign, actually means the binary number1110, which represents the instructionload.

- For example,

What’s more, it’s using ‘index’ to find the required register at a high frequency, causing a lot of middle brackets in the code, which also reduces the readability.

Let’s improve the code above into this form:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19void index() {

u8 inst = M[pc++];

u8 op = inst >> 4; // the actual instruction code

if (op == 0x0 || op == 0x1) {

int rt = (inst >> 2) & 3, rs = (inst & 3);

// mov

if (op == 0x0) { R[rt] = R[rs]; }

// add

else if (op == 0x1) { R[rt] += R[rs]; };

}

if (op == 0xe || op == 0xf) {

int addr = inst & 0xf;

// load

if (op == 0xe) { R[0] = M[addr]; }

// store

else if (op == 0xf) { M[addr] = R[0]; }

}

}Now this piece of code is a lot more cleaner and more readable, the instructions are written in hexadecimal, and the register’s index are presented with their actual name.

But if there are more instructions being added to the os, it would grow in a horrible speed. So why not improve it this way:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18typedef union inst {

struct { u8 rs: 2, rt: 2, op: 4;} rtype;

struct { u8 addr: 4, op: 4;} mtype;

} inst_t;

void idex() {

inst_t *cur = (inst_t *)&M[pc]; // current instruction

switch (cur->rtype.op) {

case 0b0000: { RTYPE(cur); R[rt] = R[rs] ; pc++; break; }

case 0b0001: { RTYPE(cur); R[rt] += R[rs] ; pc++; break; }

case 0b1110: { MTYPE(cur); R[RA] = M[addr]; pc++; break; }

case 0b1111: { MTYPE(cur); R[addr] = R[RA]; pc++; break; }

default: panic("invalid instruction at PC = %x", pc);

}

}- NB: for syntax of the code defining

inst, please refer to Bit Fields in C.

- NB: for syntax of the code defining

Now this is a really elegant and beautiful way to handle the instructions.

Though the way we handle instructions above is rather elegant and beautiful, the way used in the current version of PA is still quite different:

decode.h: line 1051

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10// --- pattern matching wrappers for decode ---

inst.c: line 751

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29static int decode_exec(Decode *s) {

int rd = 0;

word_t src1 = 0, src2 = 0, imm = 0;

s->dnpc = s->snpc;

INSTPAT_START();

INSTPAT("??????? ????? ????? ??? ????? 00101 11", auipc, U,

R(rd) = s->pc + imm);

INSTPAT("??????? ????? ????? 100 ????? 00000 11", lbu, I,

R(rd) = Mr(src1 + imm, 1));

INSTPAT("??????? ????? ????? 000 ????? 01000 11", sb, S,

Mw(src1 + imm, 1, src2));

INSTPAT("0000000 00001 00000 000 00000 11100 11", ebreak, N,

NEMUTRAP(s->pc, R(10))); // R(10) is $a0

INSTPAT("??????? ????? ????? ??? ????? ????? ??", inv, N, INV(s->pc));

INSTPAT_END();

R(0) = 0; // reset $zero to 0

return 0;

}

End of the Second Day.

- Title: PA W3 - C Programming Language Practice

- Author: Last

- Created at : 2024-06-16 10:49:08

- Link: https://blog.imlast.top/2024/06/16/nju-pa-c2-md/

- License: This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.